In May we took a class called “Computational Text Analysis with Stylometry and R” at the Digital Humanities Summer Institute at the Université de Montréal. It was run by the Krakow-based Computational Stylistics Group. Stylometry is a method that can determine an author’s “style” through counting word frequencies. Recently, in the news, it has been used to attempt to identify the “real” author responsible for Elena Ferrante’s works. While stylometry as a method has existed since the late nineteenth-century, the possibilities of performing this work assisted by computers has made it much more accessible. From early computational stylometric analysis (such as Geir Kjetsaa’s attempt to determine Dostoevsky’s authorship of unattributed texts in the late 1970s) to more recent analysis of authorship using programming packages such as “Stylo” (such as Leah Henrickson and Eleanor Dunbill’s study of authorial voice within the Trollope family and circle or Rachel McCarthy and James O’Sullivan’s refutation of Branwell Brontë’s authorship of Wuthering Heights), authorship attribution has been the most popular subfield of stylometry, but as a method, it can also help shed light on similarity and difference between works in a corpus, or translations of the same work, or continuity in a single work.

We got interested in stylometry through our interest in Dostoevsky’s narrators’ voices. Robin Feuer Miller’s 1981 book Dostoevsky and the Idiot: Author, Narrator, and Reader identifies four distinct narrative voices in The Idiot. We wondered what we could identify among the novel’s narrative voices using stylometry, and furthermore, what stylometry might tell us about Dostoevsky’s narrative voices throughout his works. In the class we took, we learned how to use the “Stylo” package that is part of the programming language R. This package enables you to upload texts and then adjust the frequency at which you are counting words. To do this work, all you need is a plain text corpus and R installed on your computer.

Unlike other kinds of textual analysis, stylometry uses very common, semantically trivial words as part of its comparisons as these are stylistic hallmarks of unconscious linguistic usage or verbal tics, so to speak. One of the first strategies of stylometry is analyzing the most commonly used words, so we had to lemmatize our corpus (lemmatization means that you remove grammatical inflection of words, so that only the lemma remains – so, for example, instead of saying “Я люблю книгу Достоевского” or “Он любит книгу Достоевского,” the lemmatized form would look like this: “Я любить книг Достоевск” or “Он любить книг Достоевск,” with the grammatically inflected forms reduced to root). In word counting, this is important because it means that different conjugated forms of the verb or declined forms of nouns and adjectives are counted as the same word, not different words. Lemmatization is thus an important step in performing stylometric analysis on a corpus of texts in a highly inflected language, such as Russian.

We used a plain text corpus of Dostoevsky’s novels and novellas that we had downloaded and cleaned from Project Gutenberg. We deliberately chose novels and novellas that were not, for example, epistolary (as in Poor Folk) or did not have other standout formal features that might mark them as different. We also wanted to make sure that the texts would be of a similar length, so we cut each longer novel into its parts and also omitted shorter works such as “A Weak Heart” or “The Dream of a Ridiculous Man.”

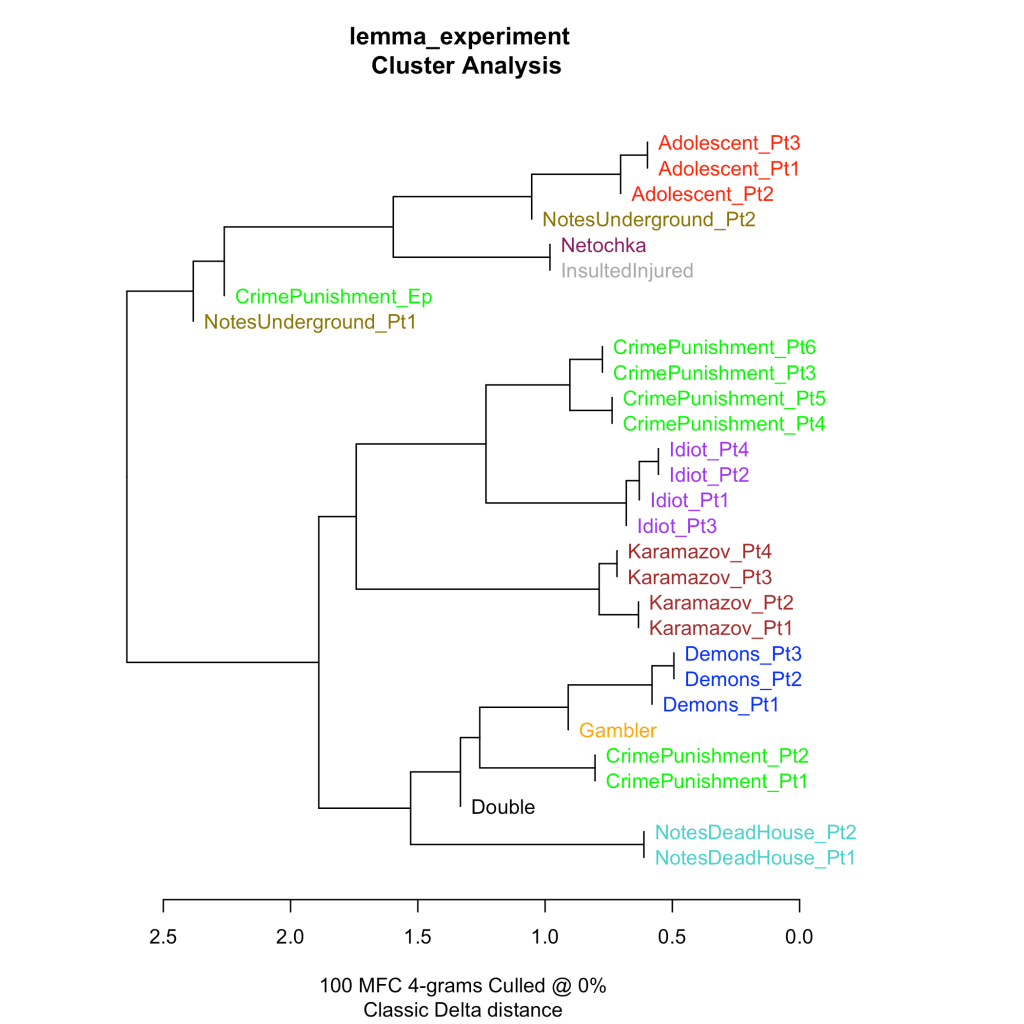

When we ran the stylo() package in R on our corpus, we first used cluster analysis to group similar works, sorted by most frequently used n*grams (groups of characters, which we set at 4 because we are using a Russian language corpus). This visualization shows a cluster analysis table that relies on the 100 most frequent characters.

In this visualization, texts that appear on the same branch are the closest in “style” or similarity based on most frequent character (MFC) counts. The distance measured on the bar at the base of the visualization corresponds to differences between the branches. So, for example, Notes from the Dead House, parts 1 and 2, is the furthest from the three parts of The Adolescent. As we adjust the MFC count, the arrangement of the texts can change.

Here all four parts of The Idiot appear in the same branch, and are therefore more similar to each other than to any of the other texts, based on 100 MFC, and the same for Brothers Karamazov, Demons and The Adolescent. What’s most noticeable is that Crime and Punishment Parts 1 and 2 are on a separate branch from the next four parts of the novel, as well as the epilogue. This separation of the different parts of Crime and Punishment suggests that, indeed, the epilogue is different than the other parts of the novel (a point that Dostoevsky scholars and critics have debated since 1867, including us), but also, intriguingly, suggests other stylistic differences between the parts.

We were also able to do bootstrap consensus and extract the data from it reflecting connections between the texts in our corpus, based on MFC ranging from 100 to 600. We could then put this into Gephi and create a network visualization of the stylometric similarities and differences between the texts. This is one of the visualizations we created, which shows 4 “neighborhood” groupings. The different colors show distinct groupings, while the weight of the network connections show degree of similarity between specific texts.

Here we can see that the Crime and Punishment epilogue is, again, distant from the rest of Crime and Punishment, as are parts 1 and 2.

Stylometry is a method we’re going to use to consider narrative voice in Dostoevsky, but the initial findings of our week in Montreal are promising and we’re excited to see what else we can uncover as we begin our stylometric adventure. We plan to present our paper on using stylometry to analyze Dostoevsky’s narrative voices at the ASEEES conference in November.

Huge thanks to our instructors, Dr. Joanna Byszuk and Jacek Bąkowski, both of the Polish Academy of Sciences and the Computational Stylistics Group. The Krakow-based group is amazing and you should check out their work.

Pingback: Introducing Digital Dostoevsky | Digital Dostoevsky