After finishing encoding our corpus at the end of last year, we’ve been working on speech network analysis. Network analysis is a method that creates a visualization of connections between elements such as characters, authors, or places within a given dataset. It’s a great method for analyzing patterns in texts like characters’ relationships to one another. It’s one of the goals we had in mind when we first thought about creating our TEI-encoded corpus of Dostoevsky’s works. The fact that we encoded speech in our TEI-edition means that we have all the necessary data for a speech network analysis at our fingertips. We are able to look at which characters speak to each other, how frequently and where they speak to one another. We can see which characters are “networked in” with which other sets of characters, and in this way we can have a sense of the underlying structures of the novel.

Data preparation is key to using the data we have encoded into our TEI edition for speech network analysis. Since we’re interested in analyzing speech, we have to isolate all its occurrences within the novel and pull this data. In this case, our RA, Dmytro Ishchenko wrote an algorithm using XSLT and XQuery to extract the speech data in Oxygen, and once he had extracted all the data, he cleaned it for us, fixing inconsistencies that were highlighted in the process. The data that Dmytro extracted had a list of speakers and targets, those who spoke, and were spoken to, in all the works in our corpus. We removed the content of the utterances, as this is not relevant for network analysis, which counts the number of speech connections between characters. We used the open-source software program Gephi to transform our data into visualizations. The first stage of our work on network analysis was a presentation we gave at our annual North American Slavic Studies conference, ASEEES.

One of the first things we realized when working on the talk was that we now have the data capability to produce networks of each section of the novels, so that not only can we produce speech network analysis of each novel as a whole but we can also look at how the networks change over time. A particularly rich subject for this kind of analysis is Crime and Punishment. While a couple of scholars (Benamí Barros Garcia and Chloë Kitzinger) have produced network analyses of that novel, neither used encoded speech as their source for network connections, and neither created networks of multiple different parts of the novels. Our conference presentation, in which we looked at networks of different parts of Crime and Punishment as well as The Idiot and Demons, was largely exploratory, but this winter we worked on a more sustained and systematic analysis of Crime and Punishment for a book chapter on “Dostoevsky and Computational Text Analysis” we’re writing for a forthcoming Routledge Companion to Dostoevsky, edited by Sarah Hudspith and Sarah J. Young.

I took on the task of further cleaning our data, and one of the first things I realized was that we had a problem with our speech encoding. First of all, since we had encoded characters’ thoughts, which were mostly undirected, we needed to remove these sections. Secondly, we had encoded some characters’ speech as undirected, in other words as not having an addressee or “target” as it is known in network analysis. Using Gephi to create network visualizations, we needed to make sure that all our speech was targeted or spoken TO another character, otherwise it needed to be removed. So I needed to go through all of Crime and Punishment and check all the utterances that were undirected and either add a target or remove the speech. The third issue was that originally we encoded some of the speakers or audience in the novel as groups, such as in scenes where characters address unnamed passersby. The Gephi visualization software cannot reproduce the data organized as a group of addressees, so I needed to remove the group tags and replace them with individual tags. This is connected to the fourth issue, which was more complicated to resolve.

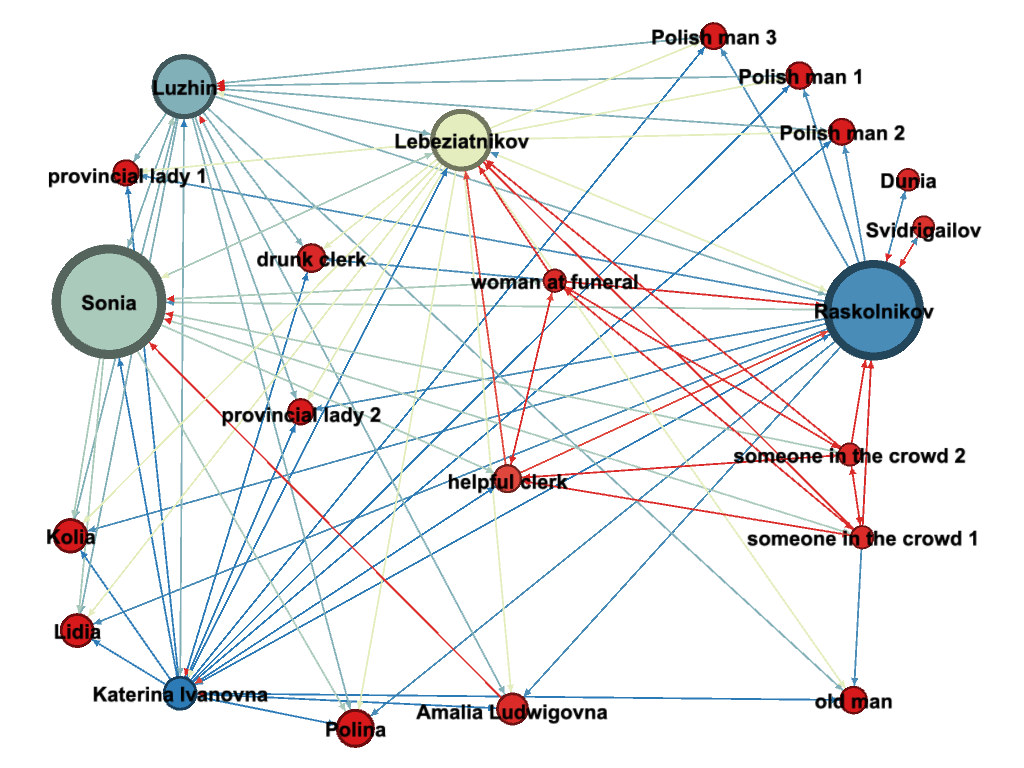

Dostoevsky is famous for his scandal scenes in which many characters appear and speak, sometimes simultaneously. Two examples of such scenes in Crime and Punishment are the funeral dinner at Katerina Ivanovna’s when Luzhin accuses Sonia of stealing the money, and the scene when Katerina Ivanovna forces her children to perform as she is dying of tuberculosis on the street. In these two scenes, many characters speak, and it is not always clear who they are addressing. Our team members who originally encoded these sections included many different characters as targets. In Gephi, each individual connection or “edge” can have only one speaker and one addressee. This means that if we wanted to express multiple “edges” or connections between speakers (or “nodes” as they are known in network analysis), I needed to create a different connection for each speaker. To get a sense of this, see our visualization of Part 5 below. I created three different Polish men, two speakers in the crowd, two provincial ladies, a drunk clerk, and a helpful clerk. None of these characters are named by Dostoevsky, but they do have one or two attributes, which we’ve tried to include in our name for these characters, all of whom speak and are spoken to.

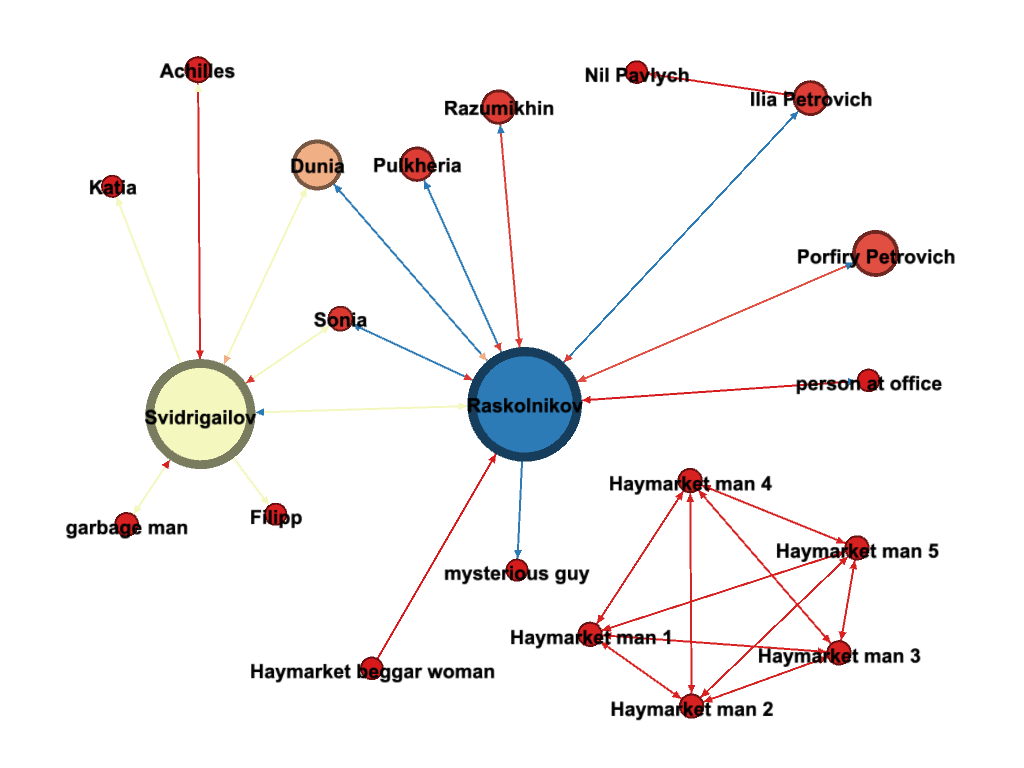

In other words, what might appear as one line of speech in the novel might appear as seven or eight different utterances or connections, one for each target. This of course creates a more orderly communication situation than Dostoevsky might have intended, but since we can work only with the textual evidence we have, that is the characters mentioned as being present in the scene, we are bound to create a neater-looking network. For instance, in the image below, from Part 6, you can see the passersby at the Haymarket as Raskolnikov is kneeling down and deciding to give himself up as a self-contained group, encoded as Haymarket Man 1-5. They speak to each other and to the world in general about Raskolnikov’s odd demeanor. Since Gephi limits the kind of data we can input to produce a visualization, we have to give up some of the nuance in our encoding. However, the benefit is a visualization that helps to reorganize data in a way that allows for a new reading of the novel. If we combine reading speech network visualizations with ordinary close reading, we can bring back the nuance to our reading of the text.